Photo (above) by JACK DELANO. Arecibo, Puerto Rico (vicinity). Sugar cane workers on a plantation (1941)

Key Terms

- Alternative Economies

- Austerity

- Bond markets

- Capitalism

- Colonialism

- Colonial capitalism

- Debt

- Enslavement and Slavery

- Extractive economies

- Hedge or Vulture Funds

- Neocolonialism

- Pension debt

- Reparations

- Sovereignty

Unit 1. Understanding Debt

The opening unit provides an introduction to consider the concept and history of debt, the general state of debt in the Caribbean, and the implications of this present state of affairs for the region’s future.

Key Questions:

- What are the politics of debt?

- How and when did debt first appear as a form of politics in the Caribbean?

- How has debt complicated the history of the Caribbean and what might be its effects on the region’s future?

David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2014).

Keith Hart, “The Anthropology of Debt,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2016, 22: 415-421.

Miranda Joseph, Debt to Society: Accounting for Life under Capitalism (University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Odette Lienau, Rethinking Sovereign Debt: Politics, Reputation, and Legitimacy in Modern Finance (Harvard University Press, 2014).

Susana Narotzky and Niko Besnier, “Crisis, Value, and Hope: Rethinking the Economy,” Current Anthropology 55 (supplement 9): S4-S16, Aug 2014.

Horacio Ortiz, “The Limits of Financial Imagination: Free Investors, Efficient Markets, and Crisis,” American Anthropologist, 2014, 116(1): 38-50.

Bartholomew Paudyn, Credit Ratings and Sovereign Debt: The Political Economy of Creditworthiness through Risk and Uncertainty (Palgrave, 2014).

Gustav Peebles, “The Anthropology of Credit and Debt,” Annual Review of Anthropology, 2010, 39: 225-240.

Stuart Hall, Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Global Transformations: Anthropology and the Modern World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Carl Wennerlind, Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution (Harvard University Press, 2011).

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Promises, Promises, A History of Debt, 10-part radio program produced by BBC (2017).

Unit 2. Debt and Theft in the Contact Period (1492-1700)

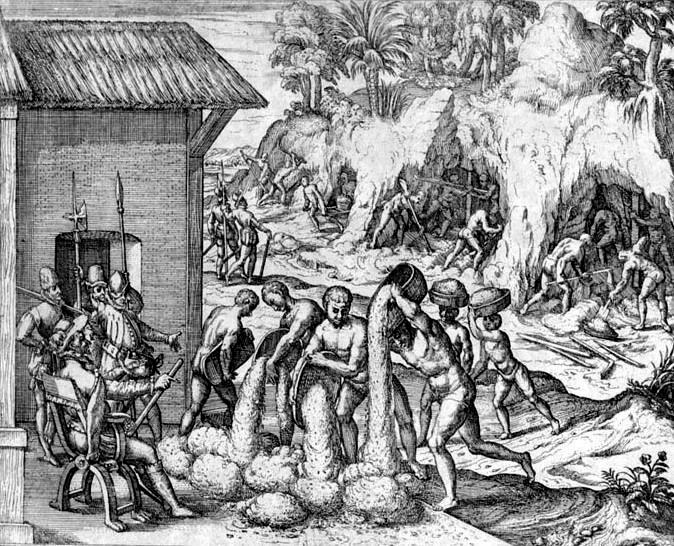

Colonial economies were designed to take goods and profits out of the Caribbean, and coloniality was based on consuming Caribbean nature, bodies, labor, land, and culture. This unit examines the relationship between colonization, genocide, European wealth creation, and debt.

Colonial economies were designed to take goods and profits out of the Caribbean, and coloniality was based on consuming Caribbean nature, bodies, labor, land, and culture. This unit examines the relationship between colonization, genocide, European wealth creation, and debt.

Key Questions:

- How did colonialism and colonial economics play a part in debt creation?

- How did genocide of indigenous groups create wealth?

- How and by whom were these policies and frameworks justified?

Francis Barker, Peter Hulme, and Margaret Iversen (eds), Cannibalism and the Colonial World (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. (Monthly Review Press, 1973).

Peter Hulme, Colonial Encounters: Europe and the Native Caribbean, 1492-1797 (Routledge, 1992).*

Melanie Newton, “The Race Leapt At Sauteurs: Genocide, Narrative and Indigenous Exile from the Caribbean,” Caribbean Quarterly (Special issue on the Garifuna People), 60(2): 5-28, June 2014.

Lizabeth Paravisni-Gebert, “Extinctions: Chronicles of Vanishing Fauna in the Colonial and Post-Colonial Caribbean.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ecocriticism, 340-357. Edited by Greg Garrard (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Irving Rouse, The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People who Greeted Columbus (New Haven, 1992).

Francisco Scarano, “Imperial Decline, Colonial Adaptation: The Spanish islands During the Long 17th Century.” in The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its People, Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano, ed (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Mimi Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean: from Arawaks to Zombies (Routledge, 2003).

Jalil Sued Badillo, “From Tainos to Africans in the Caribbean: Labor, Migration and Resistance” in The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its People, Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano, ed. (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Leif Svalesen. The Slave Ship Fredensborg (Indiana University Press, 2000).

Paul Thomas, “The Caribs of St. Vincent: A Study in Imperial Maladministration,” in Caribbean Slave Society and Economy, Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepard, ed. (New Press, 1993).

Samuel M. Wilson, Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus (University of Alabama Press, 1990).

“The Taste for Human Commodities: Experiencing the Atlantic System,” in Stephan Palmié, ed., Slave Cultures and the Cultures of Slavery, pp. 40-54 (Knoxville: University of Tennesee Press, 1995).

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Fray Agustín Iñigo Abad y Lasierra, Chapter XXX: “Carácter y diferentes castas de los habitantes de la isla de San Juan de Puerto-Rico” Historia geográfica, civil y natural de la isla de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico (1788 / 1979) Río Piedras: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico.

Bartolomé de Las Casas, A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies (Project Gutenberg EBook: 2007)

Stafford C.M. Poole, ed. In Defense of the Indians The Defense of the Most Reverend Lord, Don Fray Bartolome de Las Casas, of the Order of Preachers, Late Bishop of Chiapa, Against the Persecutors and Slanderers of the Peoples of the New World Discovered Across the Seas (Northern Illinois University Press, 1974).

Unit 3: From Bitter Sugar to Troubling Freedom: Slavery and Emancipation

The profits of slavery are directly traceable to specific families, companies and banks. When slavery was finally abolished, slave owners were paid “compensation” for their lost “capital investment,” but emancipated people were given nothing in return for their lost lives, labor, and suffering.

Key Questions:

- Who profited from slavery?

- Why is the transition from enslavement to freedom “troubled”?

- What are the colonial legacies of slave ownership and huge payouts after abolition to slave owners and others?

Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepherd, eds., Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (Jamaica and London, 1991).

Hilary Beckles, Natural Rebels: A Social History of Enslaved Black Women in Barbados (Rutgers University Press, 1989).

Hilary Beckles and Andrew Downes, “The Economics of Transition to the Black Labor System in Barbados,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 1987, 18(2): 225-247.

Thomas Bender, ed., The Antislavery Debate: Capitalism and Abolitionism as a Problem in Historical Interpretation (University of California Press, 1992).

William Darrity, Jr., “British industry and the West Indies plantations,” Social Science History, 1990, 14(1):117-149.

Howard Dodson, “How Slavery Helped Build a World Economy,” National Geographic, February 2003.

Richard S. Dunn, Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713 (University of North Carolina Press, 1966).

Ada Ferrer, Freedom’s Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Catherine Hall, Nicholas Draper, Keith McClelland, Katie Donnington and Rachel Lang, Legacies of British Slave-ownership: Colonial Slavery and the Formation of Victorian Britain (Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Thomas C. Holt, The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor, and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

Aaron Kamugisha, “The Black Experience of New World Coloniality” Small Axe, 49 (March 2016).

Natasha Lightfoot, Troubling Freedom: Antigua and the Aftermath of British Emancipation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

Bernard Moitt, Women and Slavery in the French Antilles, 1635-1848 (Indiana University Press, 2001).

Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, “Bitter Sugar: Teaching the Caribbean Plantation through the Arts.” In Re-imagining the Caribbean: Teaching Creole, French and Spanish Caribbean Literatures. Edited by Sandra Cypess and Valérie K. Orlando. (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014).

Francisco A. Scarano, Sugar and Slavery in Puerto Rico: The Plantation Economy of Ponce, 1800- 1850 (University of Wisconsin Press, 1984).

Christopher Schmidt-Nowara, “A Second Slavery?: The 19th Century Sugar Revolutions in Cuba and Puerto Rico.” Francisco Scarano, “Imperial Decline, Colonial Adaptation: The Spanish islands During the Long 17th Century.” The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its People Eds. Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Stephanie E. Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008)

Richard Sheridan, Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623-1775 (University of the West Indies Press, 1973).

Rebecca J. Scott, “Explaining Abolition: Contradiction, Adaptation, and Challenge in Cuban Slave Society, 1860-86,” in Caribbean Slave Society and Economy, Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepard, ed. (New Press, 1993).

David Olusoga “The History of British Slave Ownership has been buried: Now its scale can be revealed.” The Guardian. 11 July 2015

Manning Sanchez. “Britain’s colonial shame: Slave-owners given huge payouts after abolition.” The Independent, 23 February 2013.

Primary Sources/Multimedia

James Williams, A Narrative of the Events since the First of August, 1834 by James Williams, an Apprenticed Labourer in Jamaica. (1837). Ed. Diana Paton. (Duke University Press, 2001)

Ashton Warner, Negro Slavery Described by a Negro, Being the Narrative of Ashton Warner, a Native of St. Vincent. Ed. Susanna Strickland. (Samuel Maunder, 1831).

“How Many Britons are descended from slave owners?” BBC News, 27 Feb 2013.

UCL Centre for the Studies of the Legacies of British Slave Ownership

UNIT 4: INTIMATE BONDS AND BONDED LABOR: INDENTURE AND DEBT PEONAGE IN THE CARIBBEAN

Andrea Chung, “’Im Hole ‘Im Cahner,’” 2008, photo cut out, 24 x 17 inches

In response to the lacuna in the European colonial archive of indenture, this unit considers how Caribbean diasporic intellectuals and artists have represented the lived experience of the institution. Indenture forms part of the long history of unfree labor that began with seventeenth-century debt peonage from Europe and re-emerged in a new form after abolition when hundreds of thousands of Asians, from British India and China, were imported to perform agricultural labor across the hemisphere. An experience colored by abuse, fugitivity, and suicide, the entanglement of debt, race and labor, also includes smaller waves of indentured African and Javanese migrants who were conscripted into unfree plantation economies after emancipation.

Key Questions

- How do the descendants of indenture mourn and mediate the lived experience of the institution and represent its afterlife?

- In the mosaic of unfree labors that shaped the hemisphere, how do race and language play a role in approaches to analyzing indenture in relation to enslavement and blackbirding?

- In what present forms does debt bondage continue in the Caribbean?

Bahadur, Gaiutra. Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Goffe, Tao Leigh. “Albums of Inclusion: The Photographic Poetics of Caribbean Chinese Visual Kinship.” Small Axe July 2018; 22 (2 (56)): 35–56.

Hu-DeHart, Evelyn. “Indispensible Enemy of Convenient Scapegoat? A Critical Examination of Sinophobia in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1870s to 1930s.” in “Ed. Look Lai Walton and Tan, Chee-Beng, The Chinese in Latin American and the Caribbean, Brill, 2010.

Jung, Moon-Ho. “Coolie.” In Keywords in American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler, 64-65. New York: New York University Press, 2007.

Kempadoo, Kamala. “’Bound Coolies’ and Other Indentured Workers in the Caribbean: Implications for Debates about Human Trafficking” Anti-Trafficking Review, (9) 2017.

Look Lai, Walton. Indentured Labor, Caribbean Sugar: Chinese and Indian migrants to the British West Indies, 1838-1918, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Lowe, Lisa. “The Intimacies of Four Continents.” In Haunted By Empire, edited by Ann

Stoler. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Shepherd, Verene. Transients to Settlers: The Experience of Indians in Jamaica 1845–1950: East Indians in Jamaica in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century, Peepal Tree Press, 1994.

Ed. Torabully, Khal and Carter, Marina. Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora, Anthem Press, 2002.

Yun, Lisa. The Coolie Speaks: Chinese Indentured Laborers and African Slaves in Cuba. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008.

PRIMARY SOURCES/ MULTIMEDIA

David Dabydeen, Coolies: How Britain Re-Invented Slavery, BBC Documentary.

Ed. Dabydeen, David Kaladeen, Maria del Pilar & Ramnarine, Tina K. We Mark Your Memory: Writings from the Descendants of Indenture, 2018.

Ed. Denise Helly, Cuba Commission Report, 1876.

Jenkins, Edward. The Coolie: His Rights and Wrongs, 1871.

Fung, Richard. My Mother’s Place. DVD, 1990.

García, Cristina. Monkey Hunting, 2003.

Powell, Patricia. The Pagoda. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES (for end bibliography)

Wong, Edlie L. ”Storytelling and the Comparative Study of Atlantic Slavery and Freedom.” Social Text December 2015; 33 (4 (125)): 109–130.

Siu, Lok. Memories of a Future Home: Diasporic Citizenship of Chinese in Panama. Stanford University Press, 2007.

Tjon Sie Fat, Paul. “Old Migrants, New Immigration and Anti-Chinese Discourse in Suriname.” in “Ed. Look Lai, Walton and Tan, Chee-Beng, The Chinese in Latin American and the Caribbean, Brill, 2010.

Schuler, M. “Alas, alas, Kongo”: a Social History of Indentured African Immigration into Jamaica, 1841-1865. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

Murphy, Angela (2016). ‘This foul slavery-reviving system’: Irish opposition to the Jamaica Emigration Scheme. Slavery & Abolition, 37(3), 578-598.

Mohabir, Nalini. “Picturing an Afterlife of Indenture.” Small Axe, July 2017; 21 (2 (53)): 81–93.

Robert Wesson, ed., Communism in Central America and the Caribbean (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1982).

Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (University of North Carolina Press, 1944).

Kevin Yelvington, Producing power: Ethnicity, gender, and class in a Caribbean workplace (Temple University Press, 2010).

Unit 5: Nation-building, sovereignty and inequality

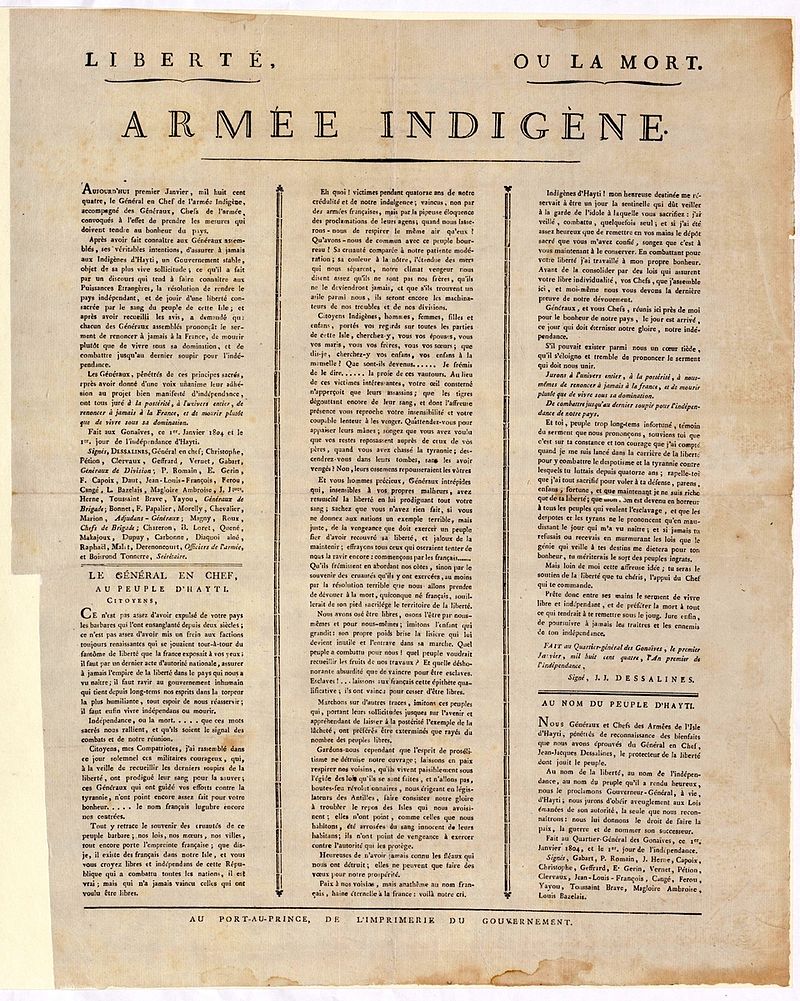

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, new political actors across the Caribbean emerged to contest European colonial rule. From the the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and the founding of the Republic of Haiti to the Cuban wars of independence culminating in the Spanish-Cuban-American War (1898), new and old colonial powers deployed debt as a form of power to limit Caribbean sovereignty and access to resources.

Key Questions:

- What role did debt play in the struggles for independence and Caribbean nation-building processes?

- How did economic inequality affect the economic and political development of Caribbean nations?

- What was the impact of colonial institutions in the state building process and how did these help or hinder these processes?

Kristy A. Belton, Statelessness in the Caribbean: The Paradox of Belonging in a Postnational World (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017).

Nigel Bolland, The Politics of Labour in the British Caribbean: The Social Origins of Authoritarianism and Democracy in the Labour Movement, 1934-54 (Ian Randle Publishers, 2001).

Yarimar Bonilla, Non-Sovereign Futures: French Caribbean Politics in the Wake of Disenchantment (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Pedro Cabán, Constructing a Colonial People: The United States and Puerto Rico, 1898-1932 (Westview Press, 1999).

CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Spring 2013, XXV, 1, Special Section on: Puerto Rico, the United States and the Making of a Bounded Citizenship, Pedro Cabán, Ed.

Norman Girvan, Foreign Capital and Economic Underdevelopment in Jamaica (Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies, 1971).

Peter James Hudson, Banker and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Franklin W. Knight, The Caribbean: The Genesis of a Fragmented Nationalism, 2nd. ed. (Oxford University Press, 1991).

Anne Macpherson, “Toward Decolonization: Impulses, Processes and Consequences since the 1930s,” in The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its People, Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano, ed (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Frances Negrón-Muntaner, “The Look of Sovereignty: Style and Politics in the Young Lords,” in Sovereign Acts: Contesting Colonialism Across Indigenous Nations and Latinx America, Frances Negrón-Muntaner, ed. (University of Arizona Press, 2017).

Francisco Scarano, “Imperial Decline, Colonial Adaptation: The Spanish islands During the Long 17th Century” in The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its People, Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano, ed. (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Deborah A. Thomas. Modern Blackness: Nationalism, Globalization, and the Politics of Culture in Jamaica. (Duke University Press, 2004).

Marion Werner, Global Displacements: The Making of Uneven Development in the Caribbean, (Wiley-Blackwell, 2015).

Juan R. Torruella, “Ruling America’s Colonies: The Insular Cases,” Yale Law & Policy Review, 2013, Article 3, 32(1).

Cyrus Veeser, A World Safe for Capitalism: Dollar Diplomacy and America’s Rise to Global Power (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002)

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Jean Michel-Basquiat, 50 cent, 1983.

Yarimar Bonilla, “Visualizing Sovereignty,” 2016, https://vimeo.com/169690419

Stephanie Black, Life and Debt, 2001.

Rosario Ferré, Sweet Diamond Dust, (Penguin, 1996).

Isaac Julien, Black Skin, White Masks (1995), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7HYPWiEr7-I

Tato Laviera, Mainstream Ethics, (Arte Publico Press, 1988).

V.S. Naipaul, V.S. Mimic Men, (New Fiction Society, 1967).

Platt Amendment, 1903

“The Insular Cases: Constitutional experts assess the status of territories acquired in the Spanish– American War”, Reconsidering Insular Cases Conference at Harvard Law School, Mar 2014 (video)

Unit 6: In focus: The Haitian Crucible

One of the most complex case studies to explore the ways that debt compromised nation-building processes in the Caribbean involves the Republic of Haiti. A result of the first successful slave revolution in history, France imposed one of the most odious debt regimes on the new “Black Republic”: it forced a state founded by formerly enslaved people to compensate French slave owners for their loss of property during the Revolution — calculated not only in terms of land but also the monetary value of enslaved human beings.

Key questions:

- What is the relationship between debt and political power in Haiti?

- In what ways did France’s debt policy provide a precedent for future post-emancipation debt regimes?

- How have European and U.S. colonial policies produced wealth at Haiti’s expense?

Greg Beckett, “The Ontology of Freedom: The Unthinkable Miracle of Haiti,” Journal of Haitian Studies 19(2): 54-74, 2013.

Susan Buck-Morss, Hegel and Haiti (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009).

Joseph Chatelain, La Banque Nationale (de la Republique d’Haïti): Son Histoire, Ses Problèmes (Imprimerie Held, 1954).

Dady Chery, We Have Dared to Be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against Occupation (News Junkie Post Press, 2015).

Laurent Dubois, Haiti: The Aftershocks of History (Henry Holt, 2012).

Alex Dupuy, Haiti in the World Economy: Class, Race, and Underdevelopment since 1700 (Routledge, 1989).

Julia Gaffield, Haitian Connections in the Atlantic World: Recognition After Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Simon Henochsberg, “Public Debt and Slavery : The Case of Haiti (1760-1915)” (Paris School of Economics, 2016).

Mats Lundahl, Peasants and Poverty: A Study of Haiti, (Routledge, 2016).

Marc Marval, La politique financière extérieur de la république d’Haïti depuis 1910. La Banque nationale de la république d’Haïti ou nos emprunts extérieurs. (Paris, Imprimerie Baron, 1932).

Richard Millett and G. Dale Gaddy, “Administering the Protectorates: the U.S. Occupation of Haiti and the Dominican Republic,” Revista/Review Interamericana, October 1976, 6(3):383-402.

David Nicholls, From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race, Colour, and National Independence in Haiti (Cambridge University Press, 1979).

Anthony Phillips and Brian Concannon, Jr., “Economic Justice in Haiti Requires Debt Restitution,” (Thesis, International Relations Center Americas Program, September 7, 2006).

Anthony Phillips, “Haiti, France, and the Independence Debt of 1825” (Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, 2008).

Brenda Gayle Plummer. Haiti and the Great Powers, 1902-1915 (Louisiana State University Press, 1988).

Robert L. Stein, “From Saint Domingue to Haiti, 1804-1825,” The Journal of Caribbean History, 1984, 19(2): 189-226.

Erin B. Taylor, “Counting on change: What money can tell us about inequality in Haiti?” (OAC Press Working Papers Series #22: 2016).

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Haiti: State against Nation: The Origins and Legacy of Duvalierism (Monthly Review Press, 1990).

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon Press, 1995).

James Weldon Johnson, “The Truth about Haiti. An NAACP Investigation,” History Matters, Crisis 5, September 1920: 217–224.

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Lenelle Moïse, “Quaking Conversation” (2014)

Banque de la République d’Haïti, Administrative and Information Documents [Documents administratifs et d’information], gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1911.

Haiti. Bureau du Conseiller Financier-Receveur Général (1930). A review of the finances of the republic of Haiti. 1924-1930: Submitted to the American High Commissioner. [Port-au-Prince].

Proclamation of the Military Occupation of Santo Domingo by the United States. The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 11, No. 2, Supplement: Official Documents (Apr., 1917): 94-96 (Published by: Cambridge University Press).

“Treaty with Haiti. Treaty between the United States and Haiti. Finances, economic development and tranquility of Haiti.” (Signed at Port-au-Prince, September 16, 1915

Ratification advised by the Senate, February 16, 1916. Ratified by the President, March 20, 1916. Ratified by Haiti, September 17, 1915. Ratifications exchanged at Washington, May 3, 1916. Proclaimed, May 3, 1916).

Inquiry into occupation and administration of Haiti and Santo Domingo: Hearing[s] before a Select Committee on Haiti and Santo Domingo, United States Senate, Sixty-seventh Congress, first and second sessions, pursuant to S. Res. 112 authorizing a special committee to inquire into the occupation and administration of the territories of the Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Washington: Govt. Print. Off., 1922.

United States Department of State / Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the

United States with the Address of the President to Congress, December 8, Haiti, pp. 334-386.

Unit 7: Gender, Reproduction and the Debt to Women’s Labor

Ingrid Pollard, The Valentine Days #1 “Negro Girls, J.V.13994”, 1891/2017. Courtesy of Ingrid Pollard/The Caribbean Photo Archive/Autograph ABP

From the moment of conquest, through slavery and the modern period women have experienced debt regimes and extraction regimes differently than men. This process has often created both particular forms of embodied and economic coercion, and strategies to resist colonial, racial, and gendered power structures.

Key Questions:

- Are there gendered forms of debt?

- How did a gendered globalization contribute to the marginalization of women in the Caribbean?

- What forms of state repressions did women face in the past, as well as in the present?

Eva E. Abraham-Van der Mark, “The Impact of Industrialization on Women: A Caribbean Case” in Women, Men and the International Division of Labor, June Nash and Maria Fernandez-Kelly, eds. (SUNY Press, 1983).

Jacqui M. Alexanderi, “Not Just (Any) Body Can Be a Citizen: The Politics of Law, Sexuality and Postcoloniality in Trinidad and Tobago and the Bahamas,” Feminist Review 48 (Autumn 1994): 5- 23.

Eudine Barriteau, The Political Economy of Gender in the Twentieth-Century Caribbean (Palgrave, 2001).

Christine Barrow, Caribbean Portraits: Essays on Gender Ideologies and Identities (Ian Randle Publishers, 1998).

Hilary Beckles, Centering Woman: Gender Discourses in Caribbean Slave Society (Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 1998).

Lynn A. Bolles, “Kitchens hit by priorities: Employed working-class Jamaican women confront the IMF,” Women, Men, and the International Division of Labor 13, 1983: 8-160.

Barbara Bush, “White ‘ladies’, coloured ‘favourites’ and black ‘wenches’: some considerations on sex, race and class factors in social relations in white Creole Society in the British Caribbean,” Slavery and Abolition 2(3) 1981.

Edith Clarke, My Mother Who Fathered Me: A Study of the Family in Three Selected Communities in Jamaica (G. Allen & Unwin, 1957).

Debra Curtis, Pleasures and Perils: Girls’ Sexuality in a Caribbean Consumer Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2009).

Cynthia Enloe, Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics (University of California Press, 1989).

Carla Freeman, High Tech and High Heels in the Global Economy: Women, Work, and Pink-Collar Identities in the Caribbean (Durham: Duke, 2000).

Gaiutra Bahadur, Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Kemala Kempadoo, Sexing the Caribbean: Gender, Race and Sexual Labor (Routledge, 2004).

Rhoda Reddock, “Women’s Organizations and Movements in the Commonwealth Caribbean: The Response to Global Economic Crisis in the 1980s.” Feminist Review 1998, 59(1): 57-73.

Pamela Scully and Diana Paton, eds., Gender and Slave Emancipation in the Atlantic World (Duke University Press, 2004).

Mimi Sheller, Citizenship from Below: Erotic Agency and Caribbean Freedom (Duke University Press, 2012).

Eileen Suarez-Findlay, Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870-1920 (Duke University Press, 1999).

Marina Vishmidt, “Permanent Reproductive Crisis: An Interview with Silvia Federici” Mute, 7 March 2013, http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/permanent-reproductive-crisis-interview-silvia-federici

Primary Sources/Multimedia

The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself (1831)

Ana María García, La operación (1983)

Mark Mark and René Bergen. Poto-Mitan: Haitian Women as Pillar of the Global Economy. (2009)

Unit 8: The Role of Law in the Production of Debt

Law has been instrumental to the colonial and neoliberal development projects that have historically fueled the growth of debt in the Caribbean. This unit addresses some of the ways that the international and US law that have been deployed in the region in the interest of capital have also allowed for the endemically indebted condition of the region.

Key Questions:

- How does law facilitate the growth of debt?

- What sorts of legal arrangements work to create indebtedness?

- What has been the relationship between colonial power structures and contemporary legal structures that have allowed for the growth of debt in the region?

Sources

Natasha Lycia Ora Bannan, “Puerto Rico’s Odious Debt: The Economic Crisis of Colonialism.” The City University of New York Law Review, 2016,19 (2): 287-311.

Benjamin Allen Coates, Legalist Empire: International Law and American Foreign Relations in the Early 20th Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Diane Lourdes Dick, “U.S Tax Imperialism.” American University Law Review, 2015, 65:1-86.

Peter James Hudson, Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Pedro A. Malavet, “The Inconvenience of a ‘Constitution [that] follows the flag … but doesn’t quite catch up with it’: From Downes v. Bidwell to Boumediene v. Bush.” Mississippi Law Journal, 2010, 80: 181-257.

Liliana Obregón, “Empire, Racial Capitalism and International Law: The Case of Manumitted Haiti and the Recognition Debt.” Leiden Journal of International Law, 2018, 31:597-615.

Cyrus Vesser, A World Safe for Capitalism: Dollar Diplomacy and America’s Rise to Global Power (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

Zenia Kish and Justin Leroy, “Bonded Life: Technologies of racial finance from slave insurance to philanthrocapital”

José L. Fusté, “Repeating Islands of Debt: Historicizing the Transcolonial Relationality of Puerto Rico’s Economic Crisis”

Unit 9: Caribbean Projects: Development, Modernization, and Socialism

The challenges to Caribbean nation-building led to a range of investments in modernizing projects. At the same time, Caribbean radical economists argued that 20th-Century models of “modernization” and “development” actually led to massive debt and impoverishment of many Caribbean countries. Some called this “extractive imperialism” or “the development of underdevelopment.”

Key Questions:

- What were the ways in which extractive imperialism made Caribbean countries worse off and what were the policy dynamics and development implications?

- How did modern development lead to socialist movements and how did colonial powers respond?

- What were the aftereffects of these socialist movements and what mark have they left in the Caribbean today?

Keith Bolender,“Cuban Perspectives on Cuban Socialism,” Socialism and Democracy 24(1) (2010).

Selwyn Cudjoe, Caribbean Visionary: A.R.F. Webber and the Making of the Guyanese Nation (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009).

Mary Dejevsky, “The Era of the Socialist Experiment is Over – But the Nostalgia Surrounding it is Growing,” The Independent (2016).

James Dietz, “Socialism and Imperialism in the Caribbean,” Latin American Perspectives 6(1) 1979: 4-12.

Tavis D. Jules, “Ideological Pluralism and Revisionism in Small (and Micro) States: The Erection of the Caribbean Education Policy Space.” Globalisation, Societies and Education, 2013, 11(2): 258-275.

Tavid D. Jules, “Going Trilingual: Post-revolutionary Socialist Education Reform in Grenada,” The Round Table 2013, 102(5): 459-470.

Stephen Kinzer, “Caribbean Communism v. Capitalism,” The Guardian, 2010.

Kathy McAfee, Storm Signals: Structural Adjustment and Development Alternatives in the Caribbean. (Boston: South End, 1991).

Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: the Making of the Black Radical Tradition, 2nd edition, (Durham, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

Euclid A. Rose, Dependency and Socialism in the Modern Caribbean: Superpower Intervention in Guyana, Jamaica, and Grenada, 1970-1985 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2002).

Barrington Salmon, “30 Years Later: Remembering Grenada’s Socialist Experiment,” New American Media (2013).

David Scott, Omens of Adversity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014)

Celia Topping,. “Cuban wheels: Cycling through the communist Caribbean.” The Independent. 12 March 2012.

J.A. Zumoff, “The African Blood Brotherhood: From Caribbean Nationalism to Communism,” The Journal of Caribbean History 2007, 41(1-2): 200-206.

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Miguel Coyula, Memories of Overdevelopment (2010)

Sara Gomez, One Way or Another (De cierta manera) (1974)

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Memories of Underdevelopment (1968)

Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place (2000)

Bruce Paddington, “Forward Ever: The Killing of a Revolution” (2013), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqvirVqrlMg

Pedro Rivera and Susan Zeig, Operation Bootstrap (1983)

Unit 10: Unnatural: Ecological Debts in the Caribbean

The extraction of natural resources and raw materials by colonial powers has resulted in what has been called “ecological debt” or the use of space and services without payment or recognition of people’s entitlement to compensation, and the degradation of local environments over long periods of time. Equally important, ecological unequal exchanges result in economic imbalances and inequities, such as that the world’s most industrialized nations produce the emissions that contribute to climate change and rising sea levels and yet the world’s most vulnerable societies are often located in the global South and increasingly pay the consequences.

Key Questions

- Why are human lives in the global north more valuable than human lives in the Caribbean?

- Why haven’t Caribbean governments politicized the environment to argue for debt cancellation and reparations?

- Why should Caribbean national communities continue to sacrifice both their people and environment’s health to sustain tourism economies while remaining mired in external debt to the global North?

Julian Agyeman, Robert D. Bullard and Bob Evans, ed., Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003).

Dana Alston and Nicole Brown, “Global Threats to People of Color,” in Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots, Robert Bullard, ed. (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1993).

Sherrie L. Baver and Barbara Deutsch Lynch, ed., Beyond Sun and Sand: Caribbean Environmentalisms (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2006).

Deborah Berman-Santana, Kicking off the Bootstrap: Environment, Development, and Community Power in Puerto Rico (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000).

Aaron Golub, Maren Mahoney, and John Harlow, “Sustainability and Intergenerational Justice: Do Past Injustices Matter?” Sustainability Science 2013, 8(2): 269-277.

Bret Gustafson. “The New Energy Imperialism in the Caribbean.” NACLA 2017, 49(4): 421-428.

Giorgos Kallis, Joan Martinez-Alier, and Richard B. Noorgard, “Paper Assets, Real Debts: An Ecological-economic Exploration of the Global Crisis,” Critical Perspectives on International Business 2009, 5(1-2): 14-25.

Hilda Lloréns, “In Puerto Rico, Environmental Injustice and Racism Inflame Protests Over Coal Ash,” The Conversation (2016).

Lirio Márquez and Jorge Fernández Porto. “Vieques: Environmental and Ecological Damage.” 2000. Diálogo.

Katherine McCaffrey. “Fish, Wildlife, and Bombs: The Struggle to Clean up Vieques.” 1 September 2009. NACLA.

David McDermott Hughes. Energy without Conscience: Oil, Climate Change, and Complicity. 2017. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Joan Martinez-Alier, The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation (Northampton, MA: Edward Edgar Publishing, Inc, 2002).

Andreas Mayer and Alpen-Andria, “Cumulative Material Flows Provide Indicators to Quantify Ecological Debt,” Journal of Political Ecology 23 (2016): 350-363.

Catalina M. de Onís, “Energy Colonialism Powers the Ongoing Unnatural Disaster in Puerto Rico,” Frontiers in Communication (2018).

Lizabeth Paravisini-Gébert,“‘All Misfortune Comes from the Cut Trees:’ Marie Chauvet’s Environmental Imagination,” Yale French Studies No. 128 (2015): 74-91.

Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, “The Caribbean’s Agonizing Seashores: Tourism Resorts, Art, and the Future of the Region’s Coastlines,” in Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, Ursula Heisse et al, ed. (New York: Routledge, 2017).

Polly Pattullo, Last Resorts: The Cost of Tourism in the Caribbean (London, Cassell / Latin American Bureau, 1996).

Laura T. Raynolds, “The Organic Agro-Export Boom in the Dominican Republic: Maintaining Tradition or Fostering Transformation?,” Latin American Research Review; Pittsburgh Vol. 43, Iss. 1 (2008): 161-184, 272.

Bonham C. Richardson. Caribbean Migrants: Environment and Human Survival in St. Kitts and Nevis. 1983. (Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press).

Timmons Roberts and Bradley C. Parks, “Ecologically Unequal Exchange, Ecological Debt, and Climate Justice: The History of Three Related Ideas for a New Social Movement,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 50(3-4) (2009): 385-409.

Andrew Simms, Ecological Debt: The Health of the Planet and the Wealth of Nations (London: Pluto Press, 2005).

Maritza Stanchich. “Ten Years After Ousting US Navy, Vieques Confronts Contamination.” 14 May 2013. Huffington Post.

Unit 11: Sold Out: Neoliberalism and Exploitative Economies

As in other parts of the world, over the last three decades, neoliberal regimes in the Caribbean have successfully shifted policies to reduce state investment in fundamental public goods such as education, health, and environment. These shifts have benefited specific sectors of capital, including real estate and finance capital.

Key Questions:

- How has banking and finance capital exerted power in the Caribbean?

- How have the development and expansion of financial institutions of colonial powers increased debt in the Caribbean and made its citizens worse off?

- How does financial capitalism manifest in economic development of the Caribbean today?

- How does debt function as a tool of “accumulation by dispossession” in the Caribbean during the era of neoliberalism?

Eitienne Balibar, “Politics of the Debt,” Postmodern Culture 23.3, 2013, http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/article/554614

Tom Barry, et al. The Other Side of Paradise: Foreign Control in the Caribbean (New York: Grove Press, 1984).

“From Commoning to Debt: Financialization, Microcredit, and the Changing Architecture of Capital Accumulation.” South Atlantic Quarterly (2014) 113 (2): 231-244.

Norman Girvan, et al, The Debt Problem of Small Peripheral Economies: Case Studies of the Caribbean and Central America (Kingston, Jamaica: Association of Caribbean Economists in collaboration with Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 1990). (Also published in Caribbean Studies 24[1-2] [1991].)

George Holmes, “Neo-liberalism, Power and the Contradictory Relationship Between Conservation NGOs and the State in the Dominican Republic,” Papers from the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers, March 2009.

Peter James Hudson, “Imperial designs: the Royal Bank of Canada in the Caribbean,” Race & Class 52(1) (2010): 33-48.*

Kiran Jayaram, “Capital Changes: Haitian Migrants in Contemporary Dominican Republic,” Caribbean Quarterly; Mona Vol. 56, Iss. 3 (Sep 2010): 31-54.

Maurizio Lazzarato, The Making of the Indebted Man: An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012).

Sharlene Mollett, “The Power to Plunder: Rethinking Land Grabbing in Latin America.” Antipode 48(2) (2016): 412-432.

Marion Werner, Global Displacements: The Making of Uneven Development in the Caribbean (New York: John Wiley, 2016).

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Esther Figueroa, Jamaica for Sale (2006).

Joseph Stiglitz in Puerto Rico: The Perils of Austerity (2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1V0PqntLDNM

Unit 12: Caribbean Education Debt

The neoliberal debt apparatus has drastic impacts on K-12 and Higher Education in the Caribbean. It produces mis-educative experiences for students, and accelerates education privatization efforts. New debt critical pedagogies within education and social movements are playing a vital role in cultivating oppositional debt consciousness and debt resistance.

Section Questions

- How does debt impact education experiences (formal/informal) in the Caribbean?

- How are debt activists developing alternative pedagogies which cultivate oppositional debt consciousness and contribute to efforts to free universities and libraries from debt regimes?

- What is the education debt owed to the descendants of slaves of the Caribbean?

Robert F. Arnove, Stephen Franz, and Carlos Alberto Torres. “Education in Latin America: From Dependency and Neoliberalism to Alternative Paths to Development,” in Comparative Education : The Dialectic of the Global and the Local, edited by Robert F. Arnove, et al., Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012, pp. 292-314.

Jason Thomas Wozniak. “Debt, Education, and Decolonization,” in Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by Michael Peters, Springer, Singapore. 2016.

Rima Brusi-Gil de Lamadrid. “The University of Puerto Rico: A Testing Ground for the Neoliberal State.” NACLA Report on the Americas, 44:2, 2011. pp.7-10.

Melissa Rosario. “Public pedagogy in the creative strike: Destabilizing boundaries and re-imagining resistance in the University of Puerto Rico.” Curriculum Inquiry, 45:1, 2015. pp. 52-68.

Alicia Pousada. “Days of reckoning for the University of Puerto Rico: the struggle to maintain the Cultural Autonomy of a Caribbean public university.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language, Volume 2012, Issue 213, 2012. pp.111–118.

Rachel M. Cohen. “Betsy DeVos is Helping Puerto Rico Re-imagine its Public School System. That has People Worried. The Intercept, 2.22.2018. https://theintercept.com/2018/02/22/puerto-rico-schools-betsy-devos/

Kristina Hinds. “Decision-Making by Surprise: The Introduction of Tuition Fees for University Education in Barbados,” in Tavis D. Jules (ed.) The Global Educational Policy Environment in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Public Policy and Governance, Volume 26) Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2016, pp.173 – 194

Nadini Persaud and Indeira Persaud. “An Exploratory Study Examining Barbadian Students’ Knowledge and Awareness of Costs of University of the West Indies Education.” International Journal of Higher Education Vol. 5, No. 2, 2016. pp.1-11.

Anthony J. Payne. (1989) “University students and politics in Jamaica.” The Round Table, 78:310, 1989, pp. 207-222.

Gloria Ladson-Billings. “From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools.” Educational Researcher, vol. 35, no. 7, 2006, pp. 3–12.

Primary Sources/Multimedia

http://reform-project.org/

In 2013, two-dozen Philadelphia schools were shuttered by city authorities in an effort to close a budget deficit. In response to these closings, Temple Contemporary commissioned artist Pepón Osorio to create a new installation specifically addressing the loss of the Fairhill Elementary School in North Philadelphia, not far from Temple University.

Papel Machete: https://papelmachete.wordpress.com/

Unit 13: Visa for a Dream: Migration and Remittances

The Caribbean is not only one of the most indebted regions in the world, it is also one of the most affected by mass migration. Migration affects debt regimes in various and sometimes contradictory ways as migrants remittances may distress sending communities while simultaneously keeping them and the state politically afloat. Migration itself may also entail massive debt, turning migrants into a new form of indentured labor.

Key Questions:

- What is the relationship between migration and debt?

- How has migration contributed to the alleviation or aggravation of sovereign debt in the Caribbean?

- What is the role that migrant labor plays in Caribbean politics today?

Kristy Belton, Statelessness in the Caribbean (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2017).

Crus Caridad Bueno, “Grassroots Development: The Case of Low-Income Black Women Workers in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic” Review of Black Political Economy; Baton Rouge Vol. 42, Iss. 1-2, (Jun 2015): 35-55.

Rosemary Brana-Shute and Rosemarijn Hoefte, “A bibliography of Caribbean migration and Caribbean immigrant communities” (Gainesville, FL: Reference and Bibliographic Dept., University of Florida Libraries in cooperation with the Center for Latin American Studies, University of Florida, 1983).

J.A. Brown-Rose, Critical Nostalgia and Caribbean Migration (New York: Peter Lang, 2009).

Mary Chamberlain, ed., Caribbean Migration: Globalised Identities (New York: Routledge, 1998).

Jorge Duany, Blurred Borders: Transnational Migration between the Hispanic Caribbean and the United States (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011)

Lauren Derby, and Marion Werner, “The Devil Wears Dockers: Devil Pacts, Trade Zones, and Rural-Urban Ties in the Dominican Republic” Nieuwe West – Indische Gids; Leiden Vol. 87, Iss. 3/4, (2013): 294-321.

Christine Du Bois, “Caribbean Migrations and Diasporas” in The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its Peoples, Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano, ed., pgs. 583- 596 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

James Ferguson, Migration in the Caribbean: Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Beyond (London: Minority Rights Group International, 2003).

Ramón Grosfoguel, Colonial Subjects: Puerto Ricans in a Global Perspective (University of California Press, 2003).

Ramona Hernández, The mobility of workers under advanced capitalism : Dominican migration to the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

Beverley Mullings and D. Alissa Trotz, “Engaging the Diasporas: An Alternative Paradigm from the Caribbean,” in New Rules for Global Justice: Structural Redistribution in the Global Economy, Jan Aart Scholte, Lorenzo Fioramonti and Alfred G. Nhema, ed. Pp. 43-56 (New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016).

Hiska Reyes, “Migration in the Caribbean: A Path to Development?” (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2004).

Alissa Trotz and Beverley Mullings, “Transnational Migration, the State and Development: Reflecting on ‘The Diaspora Option,’” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17(2) (2013): 154-171.

“Migration and the Caribbean diaspora.” (St. Michael, Barbados: AICA Southern Caribbean, 2001).

Primary Sources/Multimedia

Juan Luis Guerra, “Visa para un sueño” (1989).

Rita Indiana, “La Hora de Volvé’” (2010).

Calle 13, “Latinoamérica” (2010).

Gabby Rivera, Juliet Takes a Breath (2016)

Junot Diaz, Drown (1996) and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007)

Unit 14: The Past is not Past: The Case for Reparations

The call for reparations as a way to address the major gaps in wealth and opportunity between former colonies and colonizers has been growing across the Caribbean. In the Anglophone and Francophone Caribbean, the emphasis is on reparations for enslavement under European powers; in Puerto Rico, it refers to reparations for US colonization since 1898.

Key Questions:

- What are the arguments for reparations?

- Why have these emerged in the late twentieth century?

- How would reparations for slavery and debt in the Caribbean affect the region and the world?

Westenley Alcenat, “The Case for Haitian Reparations,” Jacobin Magazine, 14 January 2017.

Henry Balford, “£7.5 trillion for slavery,” Jamaica Observer, 22 Sept 2014.

Hilary Beckles, Britain’s Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Native Genocide (Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 2013).

Alfred Brophy, “The Case for Reparations for Slavery in the Caribbean,” Slavery & Abolition, 35(1) (2014): 165-169.

Steven Castle, “Caribbean Nations to Seek Reparations, Putting Price on Damage of Slavery.” The New York Times, October 2013.

Peter Clegg, “The Caribbean Reparations Claim: What Chance of Success?” The Round Table 103(4): 435.

Thomas Craemer, “Estimating Slavery Reparations: Present Value Comparisons of Historical Multigenerational Reparations Policies,” Social Science Quarterly, 2015 96(2): 639-655.

Alex Dupuy, “Commentary Beyond the Earthquake: A Wake-Up Call for Haiti,” Latin American Perspectives 37(3) (2010): 195-204.

Charles Forsdick, “Compensating for the past: Debating Reparations for Slavery in Contemporary France”, Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 2015, 19(4): 420-429.

Ralph Gonsalves, The Case for Caribbean Reparatory Justice (Kingstown, Saint Vincent: Strategy Forum, Inc., 2014).

Jonathan Holloway, “Caribbean Payback,” Foreign Affairs.

Robert Mackey, “France Asked to Return Money ‘Extorted’ From Haiti” New York Times, 16 August 2010.

Luke de Noronha, “Britain must honor its debt to the Caribbean Islands,” The Guardian, 19 September 2017.

Luke de Noronha, “David Cameron’s Jamaican Prison: A Show of Ignorance, Cruelty and Historical Amnesia,” Ceasefire, 1 October 2015,

Mark Weisbrot and Luis Sandoval “Debt Cancellation for Haiti: No Reason for Further Delays.” Center for Economic and Policy Research, December 2008.

EIan Steadman, “Site Traces Huge Payouts slave owners received after abolition” Wired, 27 February 2013.

Primary Sources/Multimedia

“Reparations for Native Genocide And Slavery.” CARICOM. 13 October 2015.

Unit 15: Help or Hinder? Foreign, Disaster and Opportunistic Aid

Colonizing powers, international organizations, and local national elites often grant, seek and/or are provided with aid to address structural challenges but rarely achieve this goal. Instead, aid tends to deepen unequal relations in the global economy and locally.

Key Questions:

- What is “aid” and what is its history in the Caribbean?

- How does international aid for disaster recovery hinder recovery and post-disaster change?

- What is the relationship between natural disasters and climate change and how has this contributed to the Caribbean debt?

- How has the existing debt affected the response of Caribbean islands to natural disasters?

- When did climate justice movements start growing and what has been the key achievements of these movement?

Sebastian Acevedo, “Debt, growth and natural disasters: a Caribbean trilogy” IMF Working Papers, 2014.

Mard D. Anderson, Disaster Writing: The Cultural Politics of Catastrophe in Latin America (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011).

Greg Becket, “A Dog’s Life: Suffering Humanitarianism in Port-au-Prince, Haiti,” American Anthropologist 119(1): 35-45, 2017.

Dady Chery, “Haiti’s Gold Rush: An Ecological Crime in the Making,” News Junkie Post. Global News and In-Depth Analyses, 29 November 2012.

Junot Diaz, “Apocalypse,” Boston Review, 1 May 2011. http://bostonreview.net/junot-diaz-apocalypse-haiti-earthquake

Alex Dupuy, “Foreign aid keeps the country from shaping its own future,” The Washington Post, 9 January 2011.

Levi Gahman and Gabrielle Thongs, “In the Caribbean, colonialism and inequality mean hurricanes hit harder,” The Conversation, 20 September 2017.

Jonathan M. Katz, The Big Truck That Went By: ow the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2014)

Sara Michaela Pavey, “Good Intentions and False Representations: How U.S. Humanitarian Aid Cultivates Dependency in Haiti,” (Texas State University, 2017).

Mark Schuller, Humanitarian Aftershocks in Haiti (New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press, 2016).

Mark Schuller, Killing with Kindness: Haiti, International Aid, and NGO’s (New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press, 2012).

Stuart B. Schwartz, Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Primary Documents/Multimedia

“Wesleyan Professor Alex Dupuy: Haiti Transformed into the “Republic of the NGOs” Democracy Now, 12 January 2011.

Haitian Led Reconstruction & Development: A Compilation of Recommendation Documents from Several Haitian Civil Society and Diaspora Organizations and Coalitions, 29 March 2010.

Unit 16. Getting Away with Debt: Debt Havens in the Caribbean

While most of the Caribbean suffers from debt, some islands are fueling their economies by becoming “tax havens” for the globe’s wealthy. Tax avoidance and secrecy in Caribbean jurisdictions allow the profits of global capitalism to be hidden from public taxation, sucking billions of dollars out of the global economy.

Key Questions:

- How did the idea of the Caribbean as a tax haven develop?

- Who is benefiting?

- How does offshoring contribute to the current debt in the Caribbean?

Godfrey Baldacchino, Island Enclaves: Offshoring Strategies, Creative Governance, and Subnational Island Jurisdictions (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University, 2010).

Nellie Bowles, “Making a Crypto Utopia in Puerto Rico,” The New York Times, February 8, 2018.

Ezra Fieser, “Indebted Caribbean Tax Havens Look to Tax Foreign Investors,” The Christian Science Monitor.

Peter James Hudson, Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).*

Peter James Hudson, “On the History and Historiography of Banking in the Caribbean,” Small Axe 18(1) (2014): 22-37.*

Bill Maurer, Recharting the Caribbean (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

Tami Navarro, “’Offshore’ Banking within the Nation: Economic Development in the United States Virgin Islands” The Global South 4(2) (2010): 9-28.

Ronen Palan, The Offshore World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

Nicholas Shaxson, Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World (London: Bodley Head, 2011).

John Urry, Offshoring (London: Polity Press, 2014).

Jordan Weissmann, “Should I Put My Money in Caribbean Tax Havens Like Mitt Romney Does?” The Atlantic.

Unit 17. Unpayable Debt: The Puerto Rico Case (2006-present)

Since 2015, debt crisis in the Caribbean has become equated with the travails of Puerto Rico, underscoring that the use of debt to establish new forms of colonial power in the region remains viable and efficient for capital.

Key Questions:

- How and why did Puerto Rico became one of the most indebted places in the world?

- What does Puerto Rico’s debt tell us about the rise of global finance capital?

- How is debt facilitating new colonial forms of domination and galvanining decolonial politics?

Kate Aronoff, “Puerto Rico is On Track for Historic Debt Forgiveness – Unless Wall Street Gets its Way” The Intercept, 4 October 2017.

Yarimar Bonilla, “Why Would Anyone in Puerto Rico Want a Hurricane? People think someone will get rich,” The Washington Post, 22 September 2017.

Nellie Bowles, “Making a Crypto Utopia in Puerto Rico,” The New York Times, 2 February 2018.

Nicholas Confessore and Jonathan Mahler, “Inside the Billion-Dollar Battle for Puerto Rico’s Future,” New York Times, 19 December 2015.

Nelson Denis, “The Jones Act: The Law Strangling Puerto Rico,” The New York Times, 25 September 2017.

Ismael García-Colón and Harry Franqui-Rivera, “Puerto Rico Is NOT Greece: The Role of Debt in Colonialism,” FocalBlog, 26 August 2015.

John Gendall, “A Puerto Rican Architect Explains How Rebuilding the Country Will Take More Than Brick and Mortar,” Architectural Digest, 3 October 2017.

Martín Guzman, “Puerto Rico’s debt crisis is a wake-up call. It could be crushed like Greece,” The Guardian, 8 May 2017.

Lisa Jahn and Sarah Molinari, “New Developments in Puerto Rican Economic Readjustment?” panel commentary, 2015.

Hilda Lloréns, Ruth Santiago, Carlos G. García-Quijano, Catalina M. de Onís. Hurricane María: Puerto Rico’s Unnatural Disaster. Social Justice, 22 January 2018.

Ed Morales, “The Roots of Puerto Rico’s Debt Crisis—and Why Austerity Will Not Solve It,” The Nation, 8 July 2015.

Frances Negrón-Muntaner, “The Crisis in Puerto Rico is a Racial Issue. Here’s Why,” The Root, 12 October 2017.

Frances Negrón-Muntaner, “Blackout: What Darkness Illuminated in Puerto Rico,” Politics/Letters, 2 March 2018.

Natasha Lycia Ora Bannan. “Puerto Rico’s Odious Debt: The Economic Crisis of Colonialism,” The City University Law Review, Vol. 19, Issue 2 (Summer 2016).

Melissa Rosario, “Healing the Break”: A DiaspoRican Project of Return,” Savage Minds, 9 May 2016.

Mary Williams Walsh, “After Puerto Rico’s Debt Crisis, Worries Shift to Virgin Islands, The New York Times, 25 June 2017.

Primary Sources/Multimedia

ADAL, “Puerto Ricans Under Water.”

Kate Arnoff, Puerto Rico is on Track for Historic Debt Forgiveness – Unless Wall Street Gets Its Way, The Intercept, 4 October, 2017.

Omar Banuchi and Ed Morales, “A Cartoon History of Colonialism in Puerto Rico,” Village Voice March 19, 2018. https://www.villagevoice.com/2018/03/19/a-cartoon-history-of-colonialism-in-puerto-rico/

Giannina Braschi, United States of Banana (Las Vegas, NV: Amazon Crossing, 2011).

Congressional Research Service Report on PROMESA (2016)

“Debt,” Radio Ambulante, 20 December 2016.

Julio González “The Crisis of Puerto Rico explained in 5 graphs” Global Politics and Law 22 April 2017.

“Juan González on How Puerto Rico’s Economic ‘Death Spiral’ is Tied to Legacy of Colonialism,” Democracy Now, 26 November 2015.

Naomi Klein, “The Battle for Paradise,” The Intercept, 7 April 2018.

Puerto Rico Oversight Board Website

Puerto Rico Under Water: Five Artist Perspectives on Debt, http://www.cser.columbia.edu/puerto-rico-under-water

PROMESA Bill, H.R.4900, 114th Congress (2016).

Puerto Rico’s debt crisis and its impact on the bond markets [electronic resource] : hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourteenth Congress, second session, February 25, 2016. Washington : U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2017.

Unit 18. Imagining Things: Debtless Futures

As growing debt propels even greater migrations and inequality, communities, artists, and activists are imagining other ways of living good lives and creating more horizontal political communities.

As growing debt propels even greater migrations and inequality, communities, artists, and activists are imagining other ways of living good lives and creating more horizontal political communities.

Key questions:

- What are the responses to debt regimes in the era of financial capitalism?

- What kinds of (non-monetary) currencies do Caribbean peoples use to exchange material goods, services, and to add value to their lives?

- What is the role or art, new forms of political organization, and ways of thinking about resources in building more just societies in the Caribbean?

Anna Kasafi Perkins, Justice as Equality: Michael Manley’s Caribbean Vision of Justice (New York: Peter Lang, 2010)

Tatiana Flores and Michelle Stephens, Eds. Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago. (Long Beach, CA: Museum of Latin American Art, 2017).

Carlos G. García-Quijano and Hilda Lloréns. “What Rural, Coastal Puerto Ricans Can Teach Us About Thriving in Times of Crisis.” The Conversation, May 30 2017.

Naomi Klein, Elizabeth Yeampierre, “Imagine a Puerto Rico Recovery Designed by Puerto Ricans”, The Intercept, 20 October 2017.

Hilda Lloréns. “The Making of a Community Activist.” Sapiens, Reflection 5 May 2017.

Samuel Martinez, “A Postcolonial Indemnity? New Premises for International Solidarity with Haitian-Dominican Rights”, Iberoamericana. Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Vol. XLIV: 1-2 (2014): 173-93.

Ramesh Ramsaran, “Caribbean Survival and the Global Challenge” (Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers, 2002).

Robert Rennhack. “Global Financial Regulatory Reform: Implications for Latin America and the Caribbean.” Washington: International Monetary Fund, July 2009.

Saskia Sassen, ‘Too big to save: the end of financial capitalism’, Open Democracy News Analysis, 1 April 2009.

Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation – An Argument”. In: CR: The New Centennial Review,Vol. 3, No. 3 (2003): 257–337.

Further Reading

Kehinde Andrews,. “The West’s Wealth is based on slavery: Reparations Should Be Paid.” The Guardian.

Robert Carlyle Batie, Why Sugar? Economic Cycles and the Changing of Staples on the English and French (University of the West Indies, 1976).

Hilary Beckles, “Irma-Maria: A reparations requiem for Caribbean poverty.” Jamaica Observer. 9 October 2017.

Hilary Beckles, “Reparation Issue Will Cause Greatest Political Movement If British PM Fails To Resolve, Beckles Warns,” The Gleaner, 27 September 2017.

Ericka Beckman, Capital Fictions: The Literature of Latin America’s export age (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Laird W. Bergad, Cuban Rural Society in the Nineteenth Century: the Social and Economic History of Sugar Monoculture in Matanzas (Princeton University Press, 1990).

Lynn A. Bolles, “Paying the Piper Twice: Gender and the Process of Globalization.” Caribbean Studies 29(1) (1996): 106–119.

Victor Bulmer-Thomas, The Economic History of Latin America since Independence (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Victor Bulmer-Thomas, The Economic History of the Caribbean Since the Napoleonic

Wars (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Barbara Bush, Slave Women in Caribbean Society, 1650-1832 (Indiana University Press, 1990).

Eli Cook, The Pricing of Progress: Economic Indicators and the Capitalization of American Life (Harvard University Press, 2017).

Nick Dearden,. “Jamaica’s decades of debt are damaging its future,” The Guardian, April 2013.

Isaac Dookhan, A History of the Virgin Islands of the United States (Canoe Press, 1974)

Laurent Dubois, “Confronting the Legacies of Slavery,” New York Times, October 2013.

Katie Engelhart, “The Caribbean Is Finally Going to Sue Over Slavery,” VICE, March 2014.

Carlos G. García-Quijano, John J. Poggie, Ana Pitchon, Miguel H. Del Pozo. “Coastal Resource Foraging, Life Satisfaction, and Well-being in Southeastern Puerto Rico.” Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 71, 2 (2015): 145-167.

Norman Girvan, “Extractive imperialism in historical perspective,” Extractive Imperialism in the Americas, Henry Veltmeyer, ed., pp. 49-61 (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

Frank Graziano, Undocumented Dominican Migration (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

Steven Gregory, The Devil behind the Mirror : Globalization and Politics in the Dominican Republic (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

David Griffith, Carlos G. García-Quijano, Manuel Valdés Pizzini. “A Fresh Defense: A Cultural Biography of Quality in Puerto Rican Fishing.” American Anthropologist, Vol. 115, 1 (2013): 17-28.

David Griffith and Manuel Valdés Pizzini, Fishers at Work, Workers at Sea: A Puerto Rican Journey Through Labor and Refuge (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002).

Catherine Hall. “Britain’s massive debt to slavery”, The Guardian, 27 Feb 2013.

Barry W. Higman, “African and creole slave family patterns in Trinidad” Journal of Family History 3:3 (1978): 163-180.

Robert Himmerich y Valencia, The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521-1555 (University of Texas Press, 1991)

“Historians working toward a full imperial reckoning for Britain.” The Guardian 22 November 2017.

C.L.R. James, Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1989).

Peter James Hudson, “On the History and Historiography of Banking in the Caribbean,” Small Axe 18(1) (2014): 22-37.*

Peter Hulme and Neil L. Whitehead, ed., Wild Majesty. Encounters with Caribs from Columbus to the Present Day (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Eugène Itazienne, “La normalisation des relations franco-haïtiennes (1825-1838),” Outre-mers, 2003, 90(340-341): 139-154.

Sam Jones, “Follow the money: investigators trace forgotten story of slave trade,” The Guardian, 27 Aug 2013.

Kemala Kempadoo, ed., Sun, Sex and Gold: Tourism and Sex Work in the Caribbean (Rowman and Littlefield, 1999).

Lester D. Langley, The Banana Wars: An Inner History of American Empire, 1900-1934, (The University Press of Kentucky, 1983).

Maurizio Lazzarato, Governing by Debt (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015)

Leadbetter, Russell, “ Secret Shame: The Scots who made a fortune from abolition of slavery” The Herald, 27 February 2013.

Katherine McCaffrey. Military Power and Popular Protests. The U.S.Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico. 2002 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press).

Stephen McLaren, “The Slave Trade made Scotland rich. Now we must pay our blood-soaked debts.” The Guardian.

Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (Penguin, 1985).

Manuel Moreno Fraginals, The Sugarmill: The Socioeconomic Complex of Sugar in Cuba, 1760-1860, Cedric Belfrage, trans. (Monthly Review Press, 1976).

Nigel Morris. “Justice for Britain’s former slave colonies? Caribbean leaders to ask the UK for apologies, repatriation and debt cancellation,” The Independent, March 2014.

Ivan Musicant, The Banana Wars: A History of United States Military Intervention in Latin America from the Spanish-American War to the Invasion of Panama (Macmillan, 1991).

Mark Padilla, Caribbean Pleasure Industry: Tourism, Sexuality and AIDS in the Dominican Republic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

Angus Cameron, and Ronen Palan, The Imagined Economies of Globalization (Sage, 2004).*

Iris Perez, Minnesotans rally to wipe Puerto Rico’s debt, Fox News October 4 2017

Nancy Priscilla, ed., Blacks, coloureds and national identity in nineteenth-century Latin America (University of London Press, 2003).

Ramesh Ramsaran, “Financial constraints and economic development in the Commonwealth Caribbean : the recent experience.” St. Augustine, Republic of Trinidad & Tobago (Institute of International Relations, 1983).

Ramesh Ramsaran,. “Savings and investment in the Caribbean : emerging imperatives.” St. Augustine, Trinidad: Caribbean Center for Monetary Studies (The University of the West Indies, 1995).

Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Tanzanian Publishing House, 1973).

Lomarsh Roopnarine, “Britain’s Black Death: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Genocide.” Journal of Third World Studies 32(1) (2015): 351-352.

Hymie Rubenstein, “Economic History and Population Movements in an Eastern Caribbean Valley,” Ethnohistory 24(1) (1977): 19–45.

Helen I. Safa, The Myth of the Male Breadwinner: Women and Industrialization in the Caribbean (Routledge, 2018).

David Scott, Omens of Adversity: Tragedy, Time, Memory, Justice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

Stephanie Seguino, “The great equalizer?: Globalization effects on gender equality in Latin America and the Caribbean” in Globalization and the Myths of Free Trade: History, Theory, and Empirical Evidence, Anwar Shaikh, ed. (Routledge, 2006).

Verene Shepherd, “Our Caribbean past matters too.” Barbados Today. 20 November 2017.

Verene Shepherd,. “Britain remembers its past but urges others to forget theirs, ” Jamaica Observer. 26 Nov 2017.

Lesley Byrd Simpson, The Encomienda in New Spain, (University of California Press, 1950).

Barbara L. Solow and Stanley L. Engerman, eds., British Capitalism and Caribbean Slavery: The Legacy of Eric Williams (Cambridge University Press, 1987).*

Dan Sperling, “In 1825, Haiti Paid France $21 Billion To Preserve Its Independence – Time For France To Pay It Back,” Forbes, 6 December 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2017/12/06/in-1825-haiti-gained-i…france-for-21-billion-its-time-for-france-to-pay-it-back/#397142a1312b

Antonio Stevens-Arroyo, “The Natural World of the Tainos,” and “The Religious Cosmos of the Tainos,” in Cave of the Jagua: the Mythological World of the Tainos (Albuquerque, 1988), 37-69.

Lanny Thompson, Imperial Archipelago: Representation and Rule in the Insular Territories under U.S. Dominion after 1898 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2010).

Richard Lee Turits, Foundations of Despotism: Peasants, the Trujillo regime, and Modernity in Dominican History (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2004).

Fitzhugh Turner, Communism in the Caribbean (New York: New York Tribune, Inc., 1950).

Valdés Pizzini, M. González Cruz, and J. Martínez Reyes, ed., La transformación del paisaje puertorriqueño y la disciplina del Cuerpo Civil de Conservación, 1933-1942 (San Juan, P.R.: Centro de Investigaciones Sociales, Universidad de Puerto Rico, 2011).